Many people have similar doubts on their weight loss journey: Why do some people never gain weight no matter what they eat, while every sip of cold water I drink seems to turn into fat? Is there really such a thing as “easy to gain weight” and “easy to lose weight” body types?

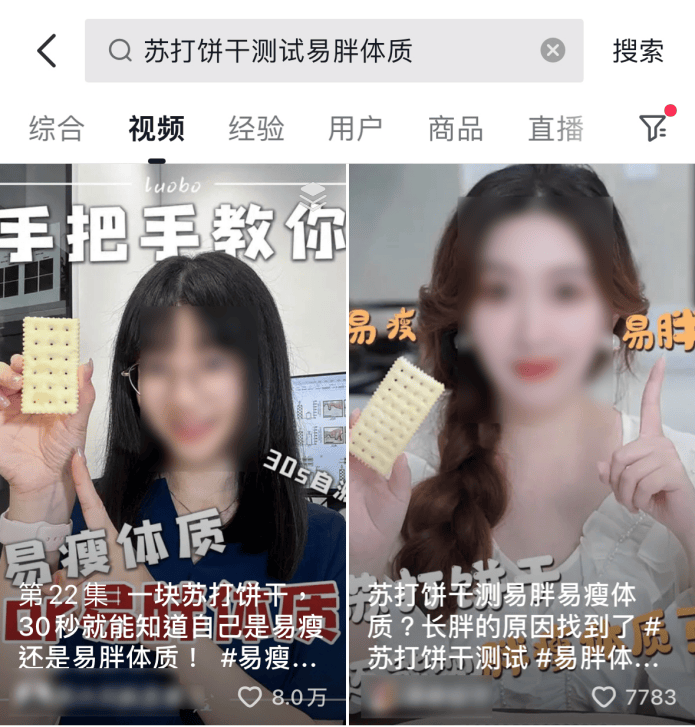

Recently, a popular video on social media about using soda crackers to identify easy weight-loss body types has addressed this question.

Take a plain soda cracker without sugar or sweeteners, put it in your mouth, chew without swallowing, and start a timer: if you can taste sweetness within 15 seconds, you have an easy weight-loss body type; if sweetness appears after 30 seconds or more, then you definitely have an easy weight-gain body type.

Image source: Social media screenshot

But is it really that simple? Can a single cracker determine if someone is easy to lose or gain weight?

People who can taste sweetness

may indeed find it harder to gain weight.

There is no clear medical definition for the so-called “easy to gain/easy to lose weight body type.”

The method of using soda crackers to test these body types originated from a book called “Gene Reboot” published in 2016 by medical doctor Sharon Mualem. Its accuracy has yet to be thoroughly researched and measured.

However, in some respects, some people are indeed more predisposed to gaining weight than others, and the method of “chewing soda crackers to detect sweetness” does have some rationale.

Soda crackers have a very simple ingredient list, mainly composed of wheat flour and corn starch, along with some yeast for food processing. The primary component of wheat flour is starch.

While starchy foods are not inherently sweet, they are an important source of sweetness—when chewing, the salivary glands secrete a substance known as “salivary amylase,” which breaks down starch into various sugar molecules.

When eating starchy foods like white bread, some people perceive them as very sweet, while others find them tasteless; this difference is due to the varying number of AMY1 gene copies responsible for salivary amylase production.

In simple terms, the more AMY1 gene copies a person has, the stronger their ability to break down starch, leading them to perceive starchy foods as sweeter. Those with fewer copies find it more difficult to taste sweetness.

There is also a correlation between AMY1 gene copy number and obesity risk.

In 2014, over thirty researchers collaborated on a study that found fewer AMY1 copies are associated with higher obesity risk and body mass index. The specific data is even more striking: individuals with more than 9 AMY1 copies have eight times the obesity risk compared to those with fewer than 4 copies.

From this perspective: those who find it harder to taste sweetness are indeed more likely to gain weight.

A subsequent study conducted a year later further explored the relationship between AMY1 copy number and obesity. Researchers identified 1,257 men aged 20 to 65 during regular health check-ups and tested their post-meal blood sugar and insulin levels.

The conclusion was that a higher number of AMY1 copies can lower insulin resistance levels. Conversely, those with fewer AMY1 copies tend to have higher insulin resistance. This insulin resistance is closely related to obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes.