Last year, my daughter went to grade 12 and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (also known as “obsessive-compulsive disorder”).

After staying in a hospital in Beijing for a month, we were discharged and returned home to attend the college entrance examination.

I thought that after my child entered university, life would go smoothly, but unexpectedly, my daughter’s condition worsened.

Every day, she would clamor to drop out of school, saying things like “life is really meaningless.”

Helpless, I had to ask for a leave of absence for my daughter so that she could rest at home before returning to school.

The child said she felt lonely at school

Who knew that after my daughter came home, she wouldn’t even leave the house, spending all day playing games in bed, not washing her face or brushing her teeth, not even showering, and only eating one meal a day.

Sometimes finding life boring, sometimes unusually excited. If we didn’t comply with her, she would have a temper, shouting, smashing things at home, even running away from home.

Despite staying in the hospital and taking medication, why doesn’t my daughter get better?

It wasn’t until I met a psychologist, who provided family guidance to us, that I understood what it means to truly love a child.

Daughter’s bipolar disorder leads to dropping out of school

My daughter started having emotional issues in grade 12.

During that time, she often couldn’t sleep all night and would bring home mineral water bottles and scraps of paper every day.

I took her to the Beijing Anding Hospital, where she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

After a month in the hospital, we were discharged. The doctor advised my daughter to continue taking medication and have regular check-ups. Little did I know, this was just the beginning.

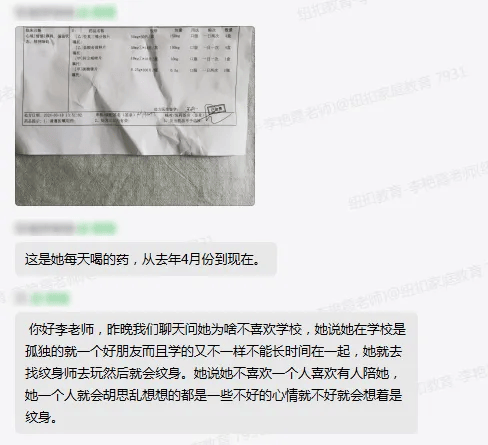

Child diagnosed with bipolar disorder and OCD at Beijing Anding Hospital

After my daughter went to university in the south, she kept talking about dropping out every few days. I didn’t agree and tried to reason with her:

“If you drop out, you will graduate later than others. When looking for work, if people find out you delayed your graduation due to dropping out, won’t that bias them against you? What about your future and job prospects?”

Although she stopped mentioning dropping out, she would often call me.

Saying things like “I’m not happy, life is so boring,” “I’m sick, I won’t be able to find a job in the future,” “I can’t see hope or a future, my life is over.” Out of concern, I had to ask for a leave of absence for her so she could rest at home before returning to school.

Child constantly seeks parents’ company to play with her

I never expected my daughter’s condition to worsen so much.

She would cry at the drop of a hat, often smashing things around the house while crying, sometimes even scratching her arms with a small knife.

One moment she would be slapping herself hard, and the next she would be excited.

She would pester me and her father to play with her. If we refused, she would throw a tantrum, shouting and yelling like she was going mad.

Although we wanted to be by her side, we are just ordinary working people. We don’t have the time to be with her constantly. If we don’t work and keep taking leave to be with her at home, how can our family survive?

What I found even more unacceptable was that at the slightest provocation or discomfort, my daughter would either go to a tattoo parlor or pierce her body.

Child easily gets stimulated

I remember one time when I took my child to a colleague’s gathering, during which a colleague advised my child to study well and understand how difficult it is for parents.

Unexpectedly, she was so triggered by this that she had an outburst in front of everyone, loudly insisting on getting a tattoo, even on her neck.

Her outburst shocked everyone, and the meal was not finished before everyone dispersed.

When we arrived at the tattoo parlor, I pleaded and reasoned with her until she finally compromised, ending up getting a tattoo on her right leg.

Child tattoos all over her body

Now, both of my daughter’s arms and the sides of her neck are covered in tattoos. We live in a small town, where people are very conservative.

When walking on the street, almost everyone who sees my daughter will scrutinize her, sometimes even comment in front of her.

Such comments would upset my daughter and make her want to get another tattoo, almost becoming a vicious cycle.

I asked her the reason, and she said something that puzzled me: “I just like this kind of pain.” What kind of talk is that? Who likes pain?

Child says she likes the pain of tattoos

Now my husband and I don’t know how to communicate with her. We are afraid of triggering her.

My daughter’s illness is not just a blow to me but also a despair.

I can’t understand why, despite being kind, working hard, and caring about my child’s education, such things happen in our family.

Even my husband and I wonder, did we do something wrong in our past lives to endure such pain in this life?

I keep blaming myself, wondering if I made a mistake in raising her at some point.

It wasn’t until I met the psychologist Li Yanxia that she pulled me out of the guilt I was feeling.

Why did my daughter develop bipolar disorder?

After becoming parents, my husband and I unconsciously compared our child to others, hoping she would outshine her peers.

Especially after she started school, our mood fluctuated with our daughter’s exam results every day.

I focused all my energy on my daughter’s studies, ensuring she had proper nutrition, encouraging her to read more, and helping her with difficult subjects, hoping she would do better.

I would be overjoyed if she performed well in exams, but if she fell out of the top five, my good mood would plummet.

My daughter’s studies became almost my entire life, and as a result, I became overly sensitive. I would be on edge about every aspect concerning my daughter, fearing it might affect her studies.

After my daughter entered grade 11, I secretly asked her homeroom teacher about the probability of her being accepted into a top-tier university. The teacher said my daughter had a good chance of getting into a prestigious university if she worked hard.

Initially, I didn’t want to tell my daughter, fearing it would pressure her, but my husband said that pressure leads to motivation. So, I passed on the teacher’s words to our daughter.

From then on, my daughter started attaching great importance to her grades and would stay up until one or two in the morning studying. It wasn’t until the psychologist intervened in our family and provided family systemic guidance that I realized:

We love our child, but our way of expressing that love is not accepted by our child.

Parents set high expectations for the child, and she also pursues perfection since childhood

Our whole family had high expectations for our daughter. To meet our expectations, our mature daughter, out of concern for us, began setting strict standards for herself, nitpicking on her flaws and mistakes.

During her adolescence, when she became sensitive and vulnerable, any decline in performance would lead to self-blame, as she felt she was not perfect enough.

Gradually, this attitude expanded beyond academics and seeped into her daily life.

She started feeling inadequate in her studies, leading to the feeling that her life as a whole was imperfect.

Believing that she knew nothing, feeling no future, and a loss of self-confidence brought her into a state of depression and anxiety.

Over time, these psychological issues took their toll.

Now, all I hope for is that my daughter can lead a normal life. But given the current situation, what can we do to make her feel loved?

How can she recover her energy quickly?

When I first contacted the psychologist, I felt utterly powerless, as if my heart was dead.

I poured out my anxiety and guilt to the psychologist, who consoled me:

“Your child’s condition may fluctuate, sometimes medication alone is insufficient.

As a mother, you must realize this is a long battle, and as parents, you must be strong.”

Yes, if I have no strength, how can I expect my child to have the strength to get better?

How to deal with the child? – Empathy

With the help of the psychologist, I reflected on the various moments of my daughter’s growth.

Previously, my husband and I would immediately point out her mistakes and reprimand her whenever she did something wrong.

My daughter had even complained that we were too nagging and talked too much.

Teacher guides parents

Therefore, I decided to change my way of interacting with my daughter, to listen to her more and speak kindly to her.

Previously, whenever I spoke, she would cover her ears and ask me to leave.

When I stopped putting myself against my child and didn’t treat her as inferior but instead incorporated four empathy techniques into our communication:

1. Listen attentively, don’t interrupt, let the child finish speaking, and carefully observe the child’s facial expressions and body language.

2. Describe the child’s emotions, for example, “You seem a bit sad.”

3. Tell the child that I understand her feelings.

For example, “I know you don’t want to go to school, just like me, I don’t want to go to work.”

Then ask her, “Do you need any help?”

4. Tell the child: Whatever happens, I will always support you.

I gradually realized that my daughter was receptive to conversations. When she was in a good mood, she was open to talking with me.

Psychologist intervenes with the daughter

The psychologist engaged deeply with my daughter and adjusted a few things:

First: Considering the specifics of the child’s bipolar disorder episodes, a psychological assistance plan was devised for her;

Second: A suitable medication plan was established, encouraging her to adhere to medication and providing psychological support on time;

Third: Teaching the child to tackle the social pressures and mental burdens brought about by bipolar disorder;

Fourth: Helping the child regain social and adaptive abilities.

The psychologist taught the child ways to alleviate internal pressure:

Talking to a counselor/friends/family, coloring books, walking in nature, regular exercise, playing with pets, puzzles, etc.

Moreover, she taught the child to maintain a journal to record her emotional fluctuations.

The journal includes:

What time she eats, sleeps, exercises, and engages in social activities each day;

The duration of sleep and activities;

Under what circumstances her emotions fluctuate.

For two months, my daughter maintained this journal, slowly understanding her emotions better.

Although she still has thoughts of getting tattoos, she can restrain herself from doing so now. Previously, she wouldn’t give up until she got a tattoo.

Child is slowly getting better

This Mother’s Day, my daughter wrote me a letter.

After reading it, I felt both touched and sad. If it weren’t for my child’s illness, I might not have realized how much she loves me.

Letter from the child to the mother

Happy Mother’s Day, Mom.

Thank you for nurturing me all these years. I understand your sacrifices, and I have also felt the changes in you and Dad during this time. You have become more cheerful and humorous. During my illness, although I had my pain, you both may have suffered more. You kept learning and accompanying me constantly. Even though I made unreasonable requests, you always tried your best to fulfill them. Words cannot express: Mom, I love you.

Child can persist in working out

That day, my daughter actually asked to go to the gym. Since her illness, this was the first time I saw such vitality in her, and I almost cried.

After this experience, I understood:

True love does not lie in expecting your child to achieve great feats; unconditional love gives a child the greatest confidence.

Life is meant for experiences; as long as my child is happy, cherishes life, and grows healthily, I am already content.

Plaque from the child’s parents to the psychologist