Recently, a pregnant mother in Sichuan discovered that her fetus may have Klinefelter syndrome during prenatal screening at the hospital. Subsequently, she sought help on social media platforms, sparking widespread social attention and discussion. Many netizens in the comment section expressed concerns about Klinefelter syndrome, even linking it to violence and criminal behavior.

So, what exactly is Klinefelter syndrome? What is a mosaic? What impact does it have? What should be done if Klinefelter syndrome is detected? Let’s delve into it together.

Klinefelter syndrome is a

genetic disorder caused by sex chromosome abnormalities

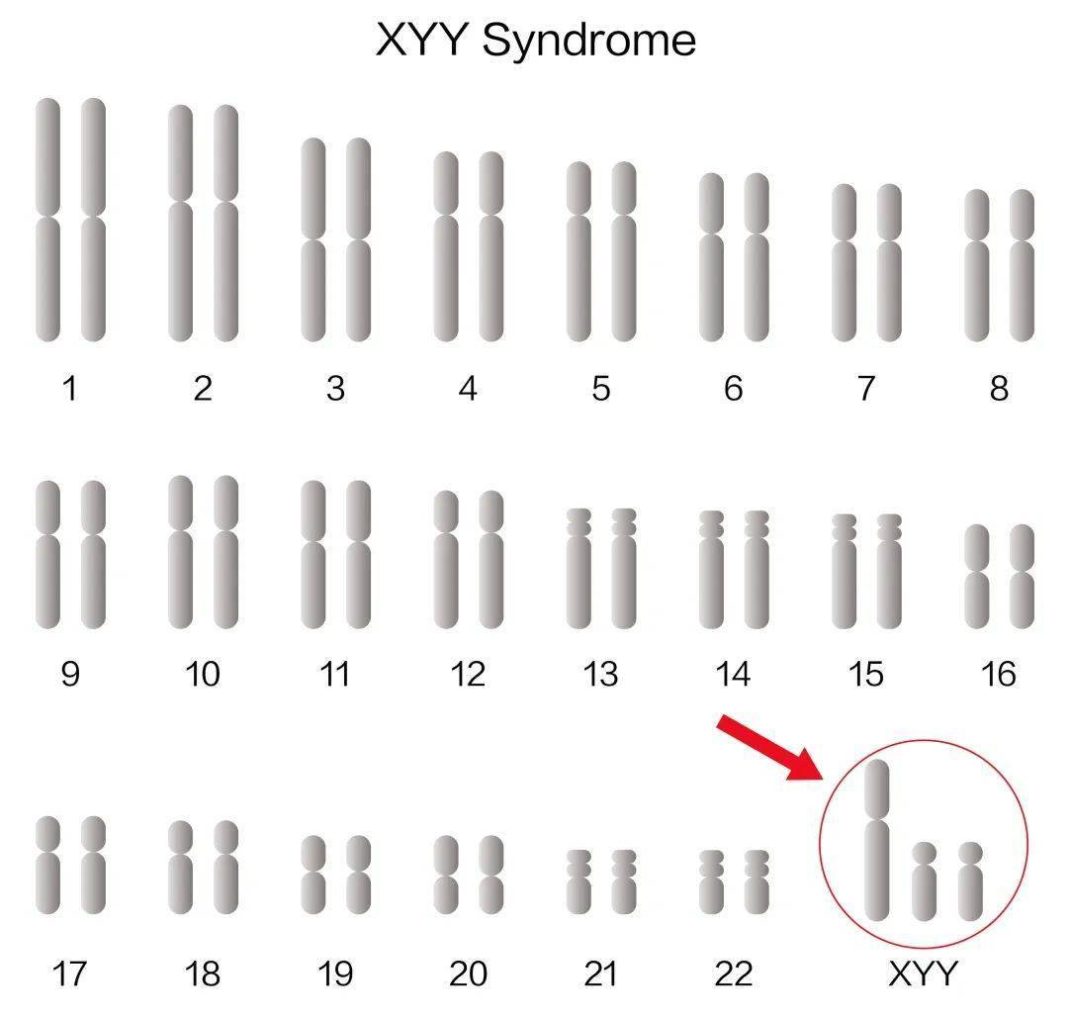

Klinefelter syndrome, also known as XYY syndrome, is a genetic disorder caused by sex chromosome abnormalities, first reported by Sandburg in 1961. This disease is one of the most common male sex chromosome disorders, with an incidence rate of about 1/1000 in male infants.

Chromosomal karyotype of Klinefelter syndrome patients

The sex chromosome of a normal male is “46, XY,” while Klinefelter syndrome patients have an extra Y chromosome, with a karyotype of “47, XYY.” The specific cause is mostly due to accidental new mutations, where the sperm of a normal father does not separate genetic material properly during the second meiotic division, resulting in abnormal sperm (YY). When this combines with a normal egg (X), it forms an abnormal zygote (XYY). A small number of patients inherit it from their fathers.

Criminal behavior in Klinefelter syndrome patients

may be the result of combined postnatal factors

Most literature studies indicate that adult Klinefelter syndrome patients mainly exhibit tall stature, normal to mildly decreased intellectual development (some patients show learning disabilities, etc.), an increased risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorders, most have normal fertility (some have low testicular function or reduced fertility).

In the 1960s, Jacobs PA and others suggested that Klinefelter syndrome patients were more likely to exhibit violent/ aggressive behavior than ordinary individuals, which was the initial source of the so-called “born criminal” label. However, subsequent studies have refuted this view. These studies indicate that the majority of Klinefelter syndrome patients do not show significant differences in social and behavioral performance compared to normal males, and that the criminal behavior of some Klinefelter syndrome patients may be the result of a combination of postnatal factors and social environments.

Due to the high clinical heterogeneity of this disease and the lack of characteristic clinical symptoms in childhood, many Klinefelter syndrome patients are misdiagnosed or even remain undiagnosed for life. In recent years, with the development of prenatal screening and diagnostic technologies, the detection rate of fetuses with a chromosomal karyotype of XYY has increased clinically.

Mosaicism is not uncommon in individuals,

and is not pathogenic in itself

If an individual has two or more different cell lines in their body, they are considered to be a mosaic, typically classified as:

Homogeneous mosaic: all cell lines originate from the same zygote, often occurring after gene mutations at different stages of embryonic development, resulting in systemic or partial mosaicism.

Heterogeneous mosaic: refers to the coexistence of two or more cell lines originating from different zygotes in the human body, common in bone marrow transplants; could also occur in cases of dizygotic twins, where one embryo dies in earlier pregnancy stages, and some cells are “absorbed” by its twin sibling.

Mosaicism can lead to different manifestations in different parts of the body (such as certain diseases only manifesting in specific areas of the body in mosaics), with mosaicism in germ cells potentially leading to inconsistencies in genetic information passed on to offspring.

In conclusion, mosaicism is a common phenomenon in nature and not unusual in individuals, and it is not pathogenic in itself. Assessing the clinical manifestations of mosaicism is challenging and generally depends on specific chromosomal/gene abnormality types, the proportion of abnormal cells, tissue distribution of abnormal cell lines, etc., to predict possible clinical outcomes.

What should be done if Klinefelter syndrome is detected?

For pregnant women with prenatal screening results indicating sex chromosome abnormalities through serological screening or non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT or NIPT-plus), samples can be collected through amniocentesis, among other methods, for karyotype analysis or tests such as CMA/CNV-seq to proceed with further prenatal diagnosis.

For families with diagnosed Klinefelter syndrome fetuses, doctors should objectively inform them of the potential clinical outcomes these children may face, allowing the families to decide whether to continue the pregnancy based on their own circumstances.

While Klinefelter syndrome cannot be cured, significant improvement in patients’ quality of life can be achieved through early intervention and scientific management, enabling them to have a life similar to that of ordinary individuals. Currently, the main intervention and management strategies include:

Educational support: providing personalized educational plans for patients, especially in language and literacy areas. Specialized educational support can help them overcome learning difficulties and improve academic performance.

Behavioral therapy: behavioral therapy and psychological counseling can provide effective assistance for issues like ADHD and attention deficits. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can help patients improve attention and impulse control.

Medical monitoring: regular health checks, particularly focusing on potential testicular dysfunction and other reproductive-related problems, as well as other potential health issues.

What other genetic disorders are there

that can be guided through screening for eugenics

In addition to Klinefelter syndrome, genetic disorders caused by chromosomal abnormalities include Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, etc., caused by abnormalities in chromosome number and cri du chat syndrome caused by structural chromosomal abnormalities. It is recommended that pregnant women undergo NIPT or NIPT-plus testing on peripheral blood samples after 12 weeks of pregnancy to screen for these common chromosomal abnormal diseases.

Furthermore, for genetic disorders caused by single gene mutations, expectant mothers can undergo carrier screening for single-gene hereditary diseases in the preconception/early pregnancy period to understand their own and their spouse’s related reproductive risks, thereby scientifically guiding subsequent pregnancy management.

Dian Diagnostic has been deeply involved in the field of reproductive health and genetics for many years, relying on high-throughput sequencing, first-generation sequencing, PCR, and other professional technology platforms, as well as a strong team of laboratory experts and report interpretation teams, to provide genetic testing projects covering the entire reproductive cycle from preconception screening, prenatal (prenatal) screening to prenatal diagnosis, and newborn screening and diagnosis, offering scientific and professional reproductive guidance for every family, safeguarding every new life.

References

[1] Sandberg A, Koepf F, Ishihara T, et al. “An XYY human male”[J]. Lancet, 1961, 278 (7200): 488-489.

[2] Expert Consensus Group on Male Reproductive Genetic Examination, Andrology Branch of the Chinese Medical Association. Expert Consensus on Male Reproductive Genetic Examination[J]. Chinese Journal of Andrology, 2015, 21(12): 1138-1142.

[3] Jodarski C , Duncan R , Torres E ,et al.Correction to: Understanding the phenotypic spectrum and family experiences of XYY syndrome: Important considerations for genetic counseling[J]. Journal of Community Genetics, 2023, 14(1):27-27.

[4] Davis SM, Bloy L, Roberts TPL, et al. Testicular function in boys with 47, XYY and relationship to phenotype. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2020; 184(2):371–385.

[5] Biesecker L G, Spinner N B. A genomic view of mosaicism and human disease[J]. Nature ReviewsGenetics, 2013, 14(5): 307-320.

[6] Cao, Y., Tokita, M.J., Chen, E.S. et al. A clinical survey of mosaic single nucleotide variants in disease-causing genes detected by exome sequencing[J]. Genome Med 11, 48 (2019).

Contact Person: Pan Hanyu

The content of this article is for health knowledge dissemination, for reference only

If you feel unwell, please seek medical attention promptly or consult a clinical doctor